If the walls of 2950 Gilbert Avenue could talk, they’d tell remarkable stories. For it was in this 19th century Cincinnati home that Harriet Beecher Stowe began her transformation from an ordinary young mother to a revolutionary writer who’d help shape American history.

Located in Cincinnati’s historic Walnut Hills neighborhood, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House stands as a reminder of the ways seemingly small and ordinary events can lead to monumental changes.

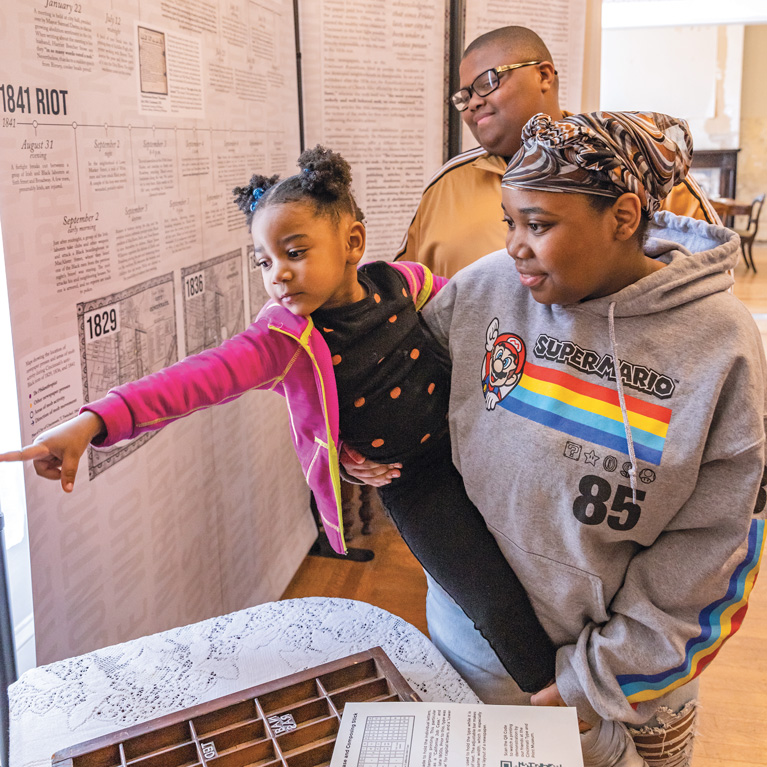

Thanks to an ongoing restoration process, ranging from the removal of 17 layers of paint from the brick exterior to installing antique windows and wallpaper, the home is beginning to look just as it did when the Beecher family lived there. And, in a way, the walls do get a chance to reveal their tales through the educational exhibits and tours set up throughout the house. From Thursday to Saturday 10 a.m.–4 p.m. and Sunday 12–4 p.m. the home is open to visitors.

When the Beecher family first moved to Cincinnati in 1832, 21-year-old Harriet was an earnest school teacher. As she met new people and explored her new city, her knowledge and perspectives began to evolve.

On the one side of the Ohio River, Harriet interacted with free Black men and women. On the other side of the river, in rural Kentucky, she met enslaved people and slave owners. She learned about the abolitionist movement from debates at the Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati and from nearby friends who were part of the Underground Railroad.

At the same time Harriet was absorbing the courageous stories of freedom-seeking African Americans and witnessing the injustices of racism, she was also harnessing her talents as a writer. Harriet joined a local writing group called the Semi-Colon Club and began penning pieces for abolitionist newspapers and mainstream magazines.

The final pieces of Harriet’s transformation began to take place with her marriage to Calvin Stowe and the building of their family. The couple was blessed with seven children, but tragically, their second youngest son Charley died at just 18 months old from cholera. This loss led Harriet to empathize with enslaved mothers whose children were stolen from them and sold at slave auctions. Her loss fueled her passion for the anti-slavery movement even more.

When the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 compounded the injustices even more, Harriet felt compelled to do something — so she harnessed the power of her voice. Pulling from real experiences, real people and real stories, she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The hugely popular book forced white people in the north, to whom slavery was a distant ideal, to reckon with its evils, leading to an avalanche of shifting ideals.

Just how big was the book’s impact? Perhaps our 16th president can tell you. Upon meeting Harriet in the midst of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln allegedly remarked, “So this is the little lady who made this big war.”

For Christina Hartlieb, executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, one of the most powerful parts of this historic site, and the story it commemorates, is how relevant the lessons are to today.

“One of my favorite moments as a tour guide took place at the end of the summer of 2020,” Hartlieb says. “I was leading a tour with a family and it had a couple of teenage girls. We were talking about how Uncle Tom’s Cabin educated a lot of white people about how horrible slavery really was. The girls remarked, ‘Oh, so the book is like social media, today.’”

Just as social media today has opened many people’s eyes to racism and injustices they don’t themselves experience, Harriet was able to do the same thing with her book in the 1800s. For Hartlieb, this connection was really powerful and drove home the importance of teaching history and learning about the power of the voice.

Hartlieb relishes the chance to get to teach about women’s history and Black history every day. “Both of these topics often get compartmentalized, but we get to show how they are key parts of our history,” she adds.

At the house, there are lots of chances for visitors to reflect, connect and even engage in activities as they take in this important history. In the Hattie and Eliza Stowe Educational Center, named for Harriet’s twin daughters who were born in the house, children can practice writing with a quill pen, making fans and playing with old-fashioned toys. Books and engaging questions are available to help spark discussions.

Even though the house focuses on the 19th century, the curators do expand their reach into the 20th century to show how history evolved. In the 1930s, the area was a thriving African American neighborhood, and the house had been converted into the Edgemont Inn, a tavern and boarding house.

At the time, traveling was dangerous for African Americans, and so Victor Hugo Green published a book called The Negro Motorist Green Book that listed safe places for people to sleep, eat and visit. The Edgemont Inn, Harriet’s former home, is one of the few Cincinnati places listed in the 1940s edition.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House isn’t the only notable place in this neighborhood near the Ohio River. On the Abolitionists and African Americans in Walnut Hills Walking Tour, you’ll learn about the rich history of this diverse and influential neighborhood.

The Cincinnati Suffrage Walking Tour leads visitors through downtown Cincinnati and covers the movement that changed the role of women in society. Walking tours are scheduled periodically. Check stowehousecincy.org for upcoming tours and programs. Wherever you chose to explore next, the story of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s impact is sure to stick with you.

Add more history to your itinerary by checking out these notable locations.

A safe haven for more than 2,000 formerly enslaved people seeking freedom, this home on the Ohio River is one of Ohio’s best documented stops on the Underground Railroad.

Travel onward to Point Pleasant to commemorate the 200th birthday of this Civil War general and two-term president. Learn about Grant’s life, including how he attended one of John Rankin’s schools.

Journey to Dayton to learn about another one of America’s powerful voices. The son of formerly enslaved people, Dunbar was one of our country’s greatest poets.

Located in Wilberforce, this vast museum features rotating exhibits and one the largest collections of Afro-American artifacts.